House of Death — The Canadian Case of a Real Estate Deal Gone Bad

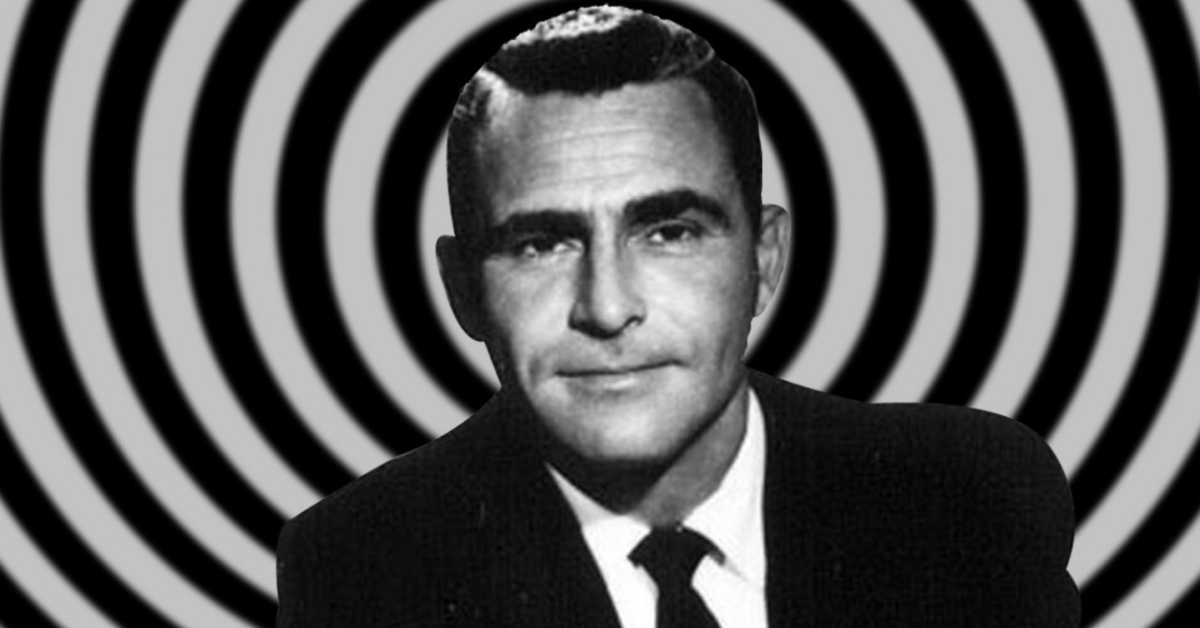

“You are about to enter another dimension, a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land of imagination. Next stop, the Twilight Zone.”

– Rod Serling, The Twilight Zone –

Would you buy a house that was the site of a grisly murder?

Is a homeowner required to disclose such potentially unsavoury historical details to a prospective buyer?

Join us as we explore these questions by reviewing the Canadian court case of a house seller who tried to keep a dark secret hidden and an innocent house buyer who tried to back out of the deal after a grizzly truth was laid bare.

Wang v Shao, 2018 BCSC 377

This case concerns the failed sale of a luxury home in Vancouver.

In the usual course of viewing the home and finalizing their deal, the buyer, Ms. Shao asked why the home was being sold by the homeowner, Ms. Wang.

Ms. Wang answered that the house was being sold because her granddaughter was changing schools.

What Ms. Wang failed to mention was the reason why Ms. Wang’s granddaughter was changing schools.

The private school Ms. Wang’s granddaughter had been attending asked her to leave following media reports that her father, Mr. Raymond Huang, was the head of an organized crime gang when news of his murder outside the front gate of the subject house property surfaced.

Upon discovering that a murder had occurred at the front gate, Ms. Shao refused to complete the purchase. Ms. Wang sued for breach of contract. Ms. Shao counterclaimed that Ms. Wang had fraudulently misrepresented the house she was selling.

The trial justice awarded judgment in favour of Ms. Shao seemingly rescuing her from having to buy the home. However, that victory was not meant to be. The Court of Appeal reversed the trial decision and ordered that the property sale should have proceeded (Wang v. Shao, 2019 BCCA 130).

In their reasoning, the Court of Appeal justices ruled there was no obligation to provide further disclosure beyond what was given as the reason for the house sale. The justices further found that Ms. Wang did not know the fact of the murder would be a legally material fact for Ms. Shao. In their decision, the appeal justices state:

If the law were now to be modified to require that upon being asked a general question like the one asked in this case, vendors must disclose all of their personal reasons and explain the causes for those reasons, even when they bear no relationship to the objective value or usefulness of the property, the door would be open to a huge number of claims. Buyers, perhaps unhappy with their purchases, could claim that information was ‘concealed’ or that a misrepresentation by omission had occurred — despite the fact the undisclosed information is, on an objective view, completely irrelevant to the value and desirability of the property. As the trial judge stated earlier in his reasons “it would be extremely difficult to determine where the line should be drawn.”

The Court of Appeal further goes on to write about the doctrine of caveat emptor:

The doctrine of caveat emptor is not intended to permit sellers to deceive buyers. It is a principle that recognizes that if buyers were required to disclose every possible feature relating not only to the physical and extrinsic qualities of their properties but also to all possible sensitivities and superstitions buyers might have, there would be no end to the resulting litigation. The doctrine places on the buyer the onus of asking specific questions designed to unearth the facts relating to the buyer’s particular subjective likes and dislikes.

According to the Court of Appeal, the answer given by Ms. Wang’s agent was “an honest answer as far as it went” and there was no requirement to “supplement” that answer with a description of the entire series of events which led to Ms. Wang’s granddaughter changing schools.

There is some potential relief to prospective home buyers worried about finding themselves in a similar situation. As we can see, the Court of Appeal hinted that had the purchaser specifically asked whether any violent deaths had occurred during Ms. Wang’s ownership of the property, the outcome might be different in this case…

Take Away

Poor Ms. Shao.

Having found a house to die for, it seemed that the previous house occupant had beat her to it.

Unfortunately for her, she would have to pay a price for failing to be more inquisitive.

Take heed of her story good reader and let the court’s decision resonate in your heart and mind as you negotiate your next house deal.

Ask the question if the answer matters to you.

Then again, perhaps some questions are best left unanswered if the past remains in the past — for should a house, yes even a house of death, be prevented from being a home again?

How many of us really know the history of the homes we live in?

Happy Halloween.

What do you think of our article? We’d love to hear from you. Leave us a message — we promise we read everything sent our way!